LA SEINE

The Seine is the fourth largest "river-tree" in France in terms of its catchment area and foliage. A remarkable tree, it has been in the spotlight in 2024—between the Olympic Games, the cleanup of its waters, and the reconstruction of Notre-Dame. Long afflicted, the tree is now healing. As the gateway for container ships and home to two major ports, the river has been heavily shaped by human activity. Its bed has been dredged to allow increasingly larger vessels to pass. We are far from the days when Sequana, the Gallic goddess of rivers and waters, was worshipped…

Like the Rhône and the Meuse, it crosses borders: one of the sources of the Oise, a major tributary in the tree, originates in Belgium. From a strictly hydrological perspective, the Seine doesn’t even have the highest flow—it is surpassed by the Yonne and the Aube. Yet its historical, cultural, and geographical significance has ensured that the name "Seine" prevailed after the centuries. The tree even touches two hydrographic tripoints—places where three river catchments meet (the Seine, the Loire, and the Meuse for instance)—which reminds me of a phenomenon called “crown shyness,” when treetops grow near each other without their leaves touching. Scientists are still confused as to why this happens.

Another curious fact: the Seine once experienced a kind of sap-rise known as a mascaret—a tidal bore that surged upstream. This dramatic wave has since vanished, lost to the dredging of the estuary.

In the collective imagination, the Seine is the quintessential French river. Its branches connect Paris, Rouen, Reims, Chartres… and it was between Tours, Paris, and Rouen that the langue d’oïl—the archaic precursor of modern French—evolved into the language spoken today. It was also along the lower Seine that the Impressionist masters painted their iconic works, inspired by the river’s reflections and light. Long before them, the Vikings used this waterway to reach the heart of the country—raiding and pillaging, but also leaving behind a cultural and linguistic legacy. (In Icelandic, the Seine is still called Signa.)

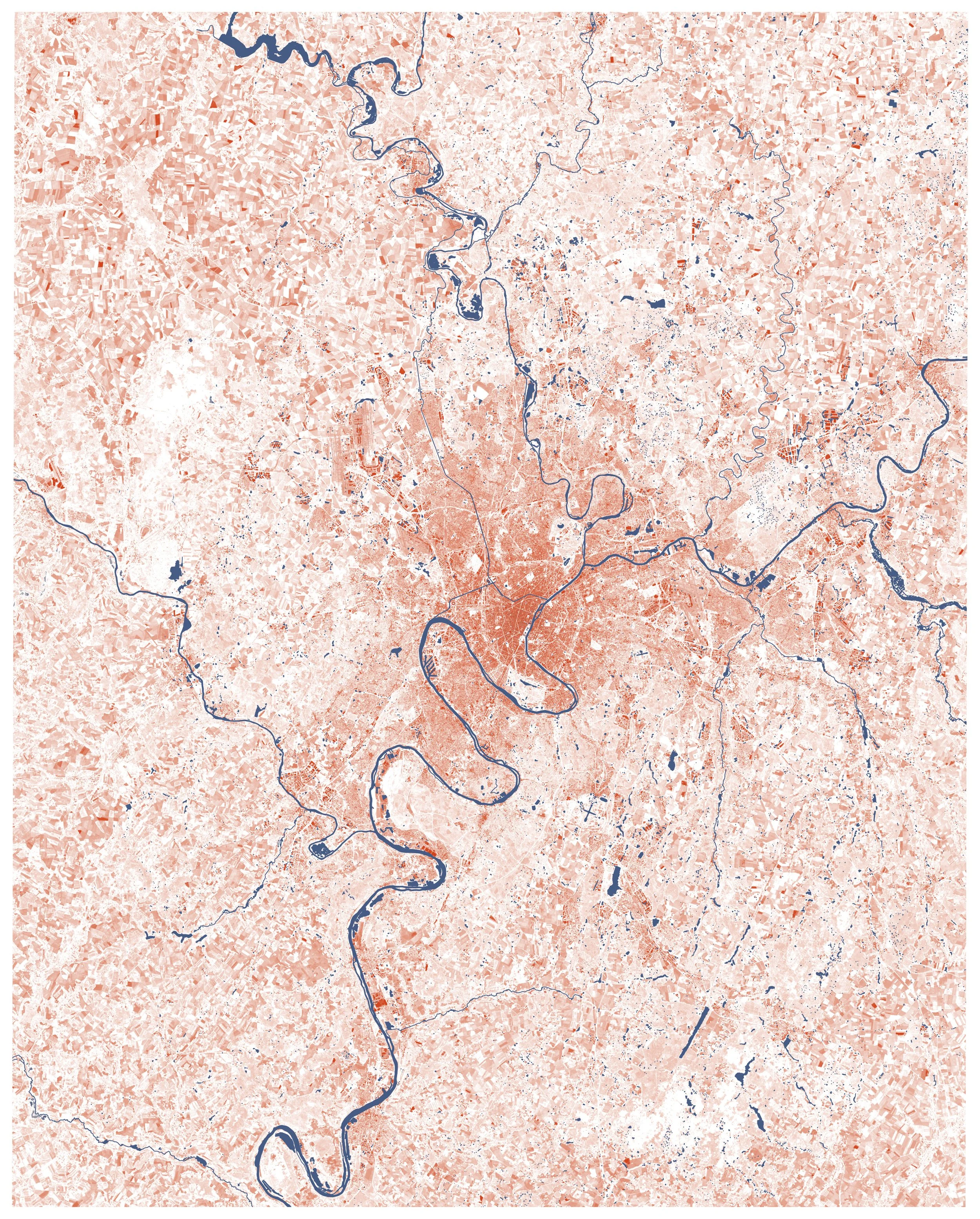

The Seine is not an enormous tree: with only 80,000 km² of foliage, moderate altitudes, and a temperate, relatively dry climate, it might seem modest, but it still holds surprises. Its floods are rare and regulated (the last so-called “century flood” occurred in 1910), thanks to dams and locks. Yet its foliage teems with life: nearly 30% of the French population, or over 20 million people, live within its reach. Its river ports, Paris and Rouen, are among the most important in Europe. Rouen, in fact, is the continent’s leading grain port, fed by the Beauce, the fertile “branch” of this tree.

Further downstream, between Paris and the sea, the trunk of the Seine meanders through flat terrain in wide loops. The river takes its time. Numerous islands emerge like long knots in the wood—the island of Saint-Denis, for instance, is 3.5 km long but only 100 to 300 meters wide. As the bed widens near the estuary, bridges grow fewer, but ocean-going ships become more frequent. The Normandy Bridge, a concrete giant, and the older Tancarville Bridge left such a mark on the landscape that in Normandy, clotheslines are still nicknamed Tancarvilles.

So, which tree best represents the Seine? Without a doubt: the common ash, Fraxinus excelsior. Common in the region, it is flexible and strong. It was once favored for making oars. It recalls the age of Viking raids and the bustling river trade of the Middle Ages. A tree of movement, memory, and resilience. A tree worthy of symbolizing this great river—tamed, yet powerful.