THE OKAVANGO

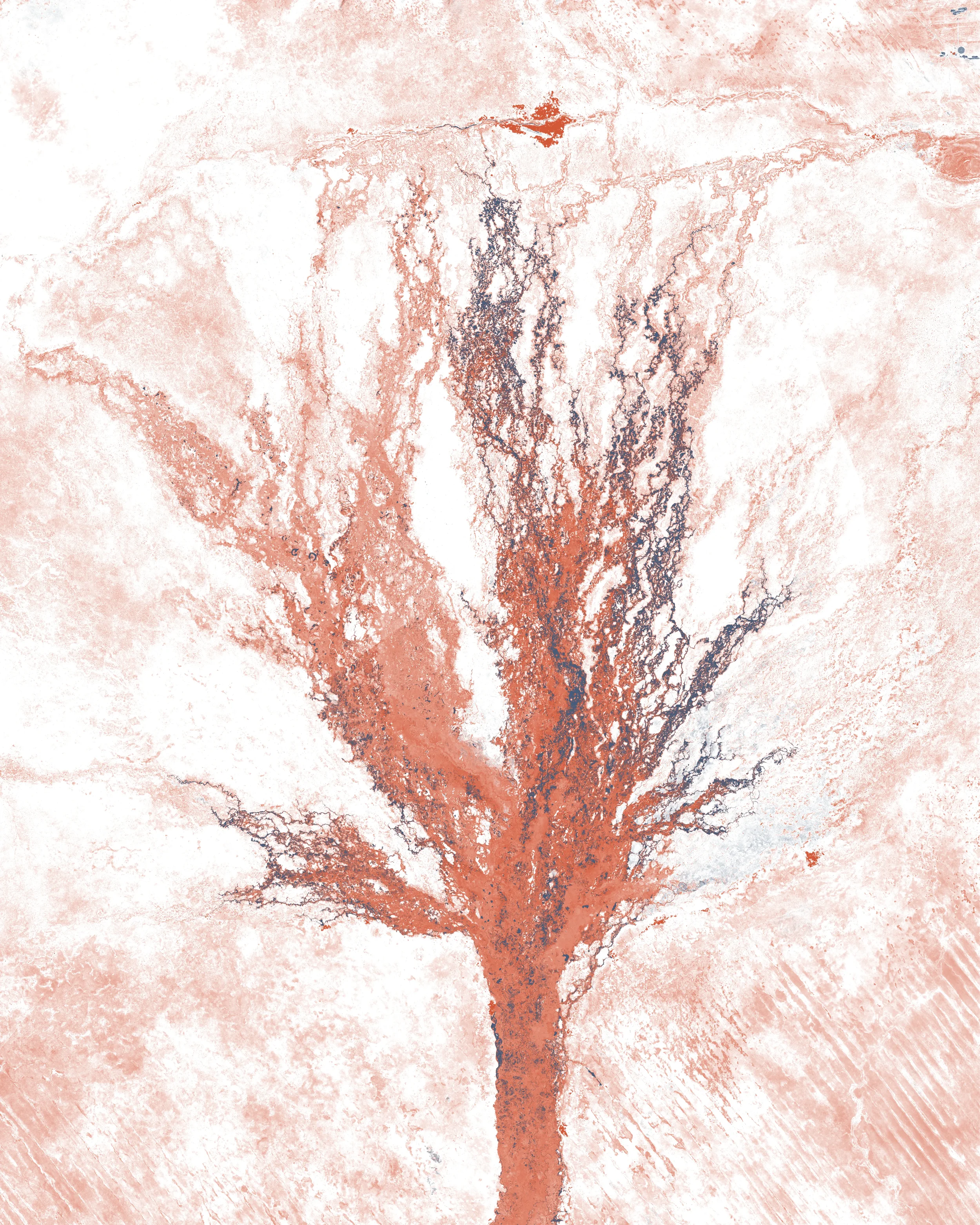

Seasonally flooded areas are shown in light blue on the map

If the Indus juniper, Juniperus Indus, is a miracle river for the people who live in its fertile, irrigated valley, the Okavango can undoubtedly claim the same title, but it is an even more exceptional miracle, full of surprises.

Every year during the southern summer, the river swells with water from the first rains of January, which come from the highlands of Angola in the west and then travel for over a month to cover the first 1,000 kilometers of the river. This water eventually reaches the delta and then takes another four months to travel its 250 kilometers, passing slowly, filtered through the plants and numerous branches of the delta, and infusing the parched land with its life-giving power.

The entire region then comes back to life : the delta triples in size and attracts animals from hundreds of kilometers away, creating one of the largest concentrations of wildlife in Africa. Thus, African elephants and buffalo, black wildebeest, hippopotamuses, Nile crocodiles, lions, cheetahs, leopards, hyenas, wild dogs, and white and black rhinos—to name just a handful of the continent's iconic species—gather here, in the middle of what was a dry and desolate place just a few weeks ago. Where the river ends, life begins, but the river doesn't really end.

If you've already skimmed through the portraits of some of the river trees presented here, something about this hydro-botanical map of the Okavango should surprise you: it has a crown, it has branches, it has a trunk and roots, but... where is the sea?

Could it be a case of an aerial tree, growing above ground? The river originates at 1,788 meters above sea level and ends its course almost 1,000 meters above sea level. Even stranger, once it reaches the delta, a small part of the water continues its journey not into the sea but into water arms, thin, seasonal roots that boldly connect—violating the founding principles of tree anatomy studied so far—to other seasonal hydrological systems: the pans.

Pans are ancient large lakes, now dry, often covered with salt, but which can get a taste of their past life during a season of intense rainfall. Irrigated with sap, life, and water from channels coming from adjacent river systems, they briefly fill with water. Grasses grow there, plants bloom, and animals come to live there for a while. In the case of the Makgadikgadi Pans seen here, the water comes from the Okavango, carried by a river called the Boteti, a rebellious root of the river delta that benefits from the exceptionally flat topography of the Kalahari Basin to escape the rules of gravity that normally apply to rivers. Are the pans an outgrowth of the tree, a peripheral organism, or another living being in symbiosis with its neighbor?

The Kalahari Basin is the geographical answer behind the morphology of this strange tree: forming a vast depression in the middle of southern Africa, one and a half times the size of Texas, it is an endorheic basin, i.e., a watershed with no outlet to the sea. There are thousands of these on Earth—mainly in continental and arid regions—but few of this size, with the added bonus of a fantastically colorful delta home to thousands of animal and plant species.

What unusual tree could possibly match this strange river? I suggest the African baobab, Adansonia digitata : an iconic tree of southern Africa that seems to carry the entire weight of the region’s natural history on its enormous trunk and which, in a way, also seems to defy gravity, just like the Okavango. Deeply adapted to aridity, it loses its leaves during the driest part of the year, earning it the nickname “upside-down tree”—its bare branches resemble roots—a nickname quite fitting for the Okavango, with its disproportionate delta that will never reach the sea. In addition to being a tree of myth and legend in Africa, the baobab has a rare characteristic that allows it to store water in ways that defy imagination: its trunk can reach 7 meters in diameter when it fills with water to withstand the dry season. When the Okavango seems to dry up and its flow weakens once winter arrives, don't look far: it's hiding in the baobabs.