A visual and geographic walk in Delhi’s rich greenery, a collection of moments and people, working, eating, exercising or just sleeping in the many gardens of the city, legacy of the centuries, from the early persianate age in India to the last decades of British Raj and finally, independent India.

Delhi is a “city of cities” they say. But I think a case could be made that Delhi is also a “cities of gardens”. A glance at the map is enough to reveal how deeply gardens are inscribed in the city’s history. Many of today’s neighbourhoods still carry names that echo a greener past: Shalimar Bagh, Punjabi Bagh, Rani Bagh—toponyms ending with bagh, the Persian word for garden. Others follow the same logic in English: Green Park, Gulmohar Park, Dilshad Garden, Rajouri Garden.

Some of these gardens have endured. Aurangzeb’s Sheesh Mahal Garden, where the Mughal emperor was crowned, was inspired by Kashmir’s famed Shalimar Garden and eventually lent its name to the entire surrounding neighbourhood: Shalimar Bagh. Behind these names, which today surface casually on Google Maps or social media feeds, once lay real places, magnificent, fabled gardens that often appear on centuries-old maps.

Bada Gumbad, (1490 CE), surrounded by trees of Lodhi Garden

But landscapes, as history reminds us, are never permanent, urbanscapes even more so. Many of these gardens have likely been swallowed by the unchecked waves of concrete that have swept across Delhi in recent decades. Outside India especially, the city is often imagined as a bleak, oppressive sprawl: endless grey expanses of mineral, hostile urbanity. If some parts of the city do indeed conform with this idea, we’ll see how and why later on, the fact that Delhi is a « City of Gardens » still holds true even today. It is, in fact, one of the greenest capitals of Asia: according to the Delhi Parks and Gardens Society, the National Capital Region boasts some 18,000 parks and gardens, amounting to roughly 8000 hectares in area, or a square of 9 km each side.

Having grown up and spent most of my life in France, I have always been struck by the sheer abundance of life in Delhi. Even the smallest parks have their familiar cast of characters: parakeets, black kites, common mynas, sparrows, jungle babblers, red-wattled lapwings—and, of course, monkeys, my greatest source of entertainment whenever I walk through these green pockets of the city.

Banyan tree and ruins, garden of Feroz Shah Kotla

The region of Delhi is one of unsuspected biodiversity thanks to its greenery: being located at the northern end of the 2 billion year old Aravalli Hills, it is still heavily forested in some parts of the range that were protected from urban sprawl. In fact, I have been to these areas, walked on Delhi’s green backbone, a mere 20 minutes drive from the outskirts of the city. The area is dominated by scrublands with short trees where, so I was told by wildlife experts working there, hyenas, leopards, nilgai, porcupine, jackal, peafowl, and many other species of birds and reptile thrive, just a few kilometers away from crowded malls, dense settlements and congested roads.

But before being the 30 million people metropolis it is today, this region, at the crossroad of the Aravalli hills, the Alluvial plain and the Yamuna flood plain, must have had been an incredible sight to behold. What is today urban development, shopping malls and industrial disctricts, was at that time nothing but wilderness, woodlands, shrublands, wetlands and meadows, with the flora and fauna of these three ecoregions, of which a fraction is left today.

Aravalli Hills landscape near Delhi

Many of these native species can still be found in Delhi’s parks and gardens, which offer Dilliwale a brief reprieve from the city’s relentless pace. Yet a careful observer soon notices a stark imbalance. Some parts of Delhi are markedly greener, lusher, and more hospitable than others, creating striking contrasts in living conditions. For those who believe access to nature is a basic right, the Indian capital can feel deeply unsettling. Its socio-spatial segregation becomes painfully visible when viewed through the lens of greenery and access to gardens.

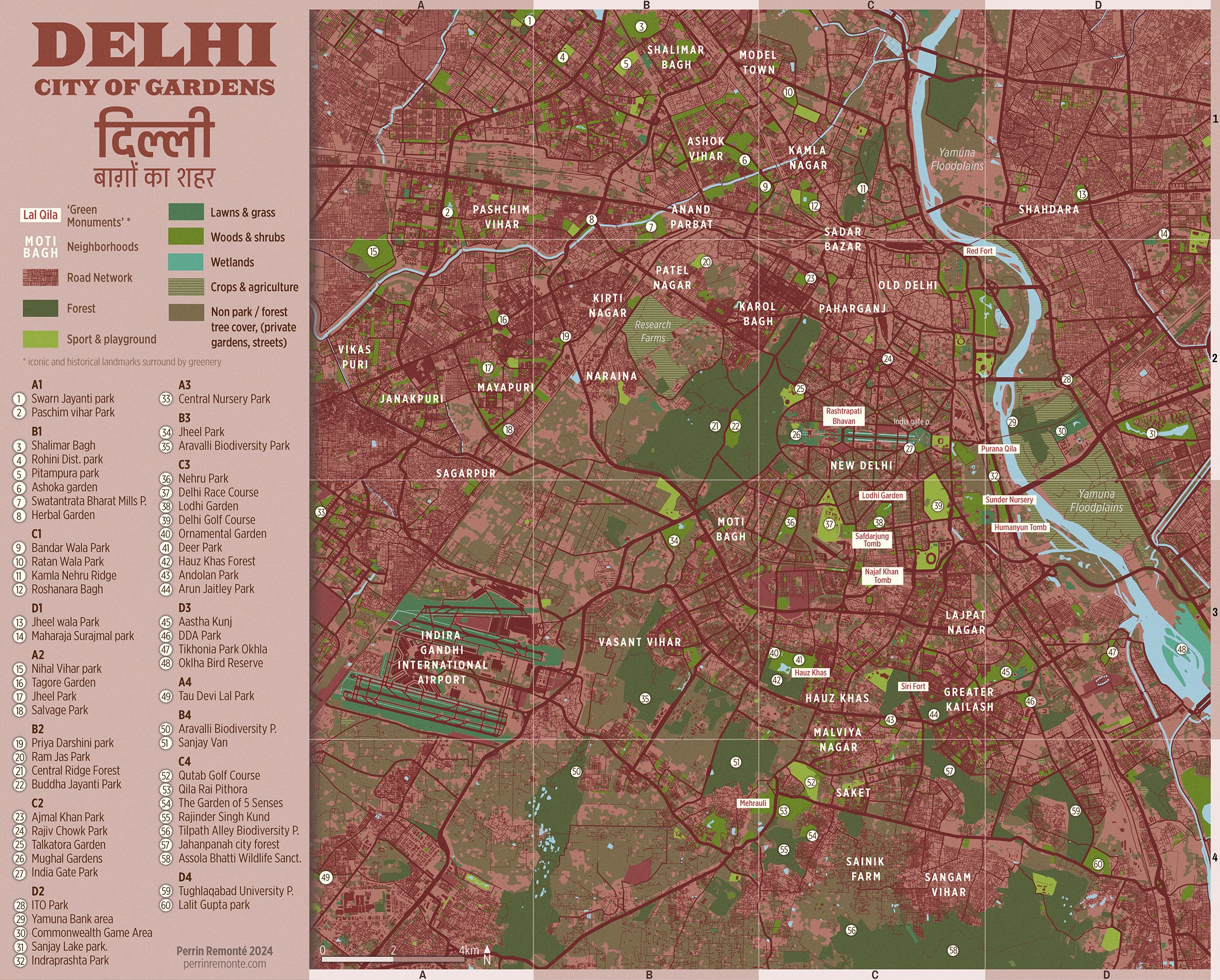

At this point, you may be wondering how all these points come together. And since few tools explain space and relationships better than a map, I offer one here: a map I made as a guide to Delhi’s green geography. It features sixty-two green spaces—only a fraction of what exists—ranging from iconic gardens to neighbourhood parks, forests, “green monuments,” and even trees growing in private gardens. A cartography of places, of inequality, memory, and daily life.

Now, browse this map and let images come to your mind: Delhi’s greenery—the Loo, this hot wind of summer sweeping throught the foliage—old monuments surrounded by leafy, tranquil treescapes, silent tombs and forts nested in groves of Babul trees, Gulmohar, Peepal, Amaltas…

It is a cartography of these green moments I am sharing with you, where to find them, what exactly awaits the wanderer in these different parks and woods, how they are laid out spatially and how large or tiny they can be…

The second best thing after a map to tacke this topic is a photo series. Let’s dive in!

Playful colours

Any patch of grass in Delhi is constantly at risk of seeing young boys and teenagers flocking to play cricket on it. Groups of boys –with no girls in sight– enthusiastically play cricket at any time of the day, loudly cheering on the trampled and parched grass whenever one team scores.

The only other thing that may come close to cricket in terms of popularity among the indian youth may be social media, more specifically, making trendy videos in parks, in front landmarks, and four century old walls, like this one pictured here in Isan Khan’s Tomb.

That is yet another kind of green moment.

Sleeping dogs and men past forty absorbed in card games are the essential ingredients in Delhi’s park cocktail.

A Hip Hop dancer practicing in a Pavillion of Deer Park, near Hauz Khas.

Even dead trees can become playgrounds, provided they meet the right audience.

A mother watching over her kids, in Sunder Nursery.

A boy holding a cricket bat, in front of a Banyan in Roshanara Bagh, North Delhi.

Just missed the ball. It doesn’t matter. These kids are playing all day long.

Playing cricket in a small park of Ashok Vihar, North Delhi.

Opulence

In Delhi, money has a colour: it’s green. No, it’s not about the rupee notes, it’s about the trees. Just like most metro cities, but even more so in Delhi, wealthy and affluent neighborhoods are considerably greener and dotted with trees providing a soothing urban environment as well as shade during the hottest months. But the greenest moments are kept between tall, heavily guarded and private walls.

Even in the scorching heat of may, servants of this bangalow near Lodhi Garden make sure the plants stay green and healthy, under the shade of a towering Banyan, on the right.

Lutyens Delhi, also known as ‘New Delhi’, is the largest planned colonial city of history and trees sure are a big part of it. At a time when Britain had its hand on 25 percent of the world, tree species from everywhere were brought to create these impeccable avenues lined with now old, matures trees and their bungalows where the capital’s diplomats, politicians and high profile people live.

In Sainik Farm, an affluent neighbourhood of South Delhi, most (if not all) houses have their own small ‘bunker’ with a guard standing inside.

Here people don’t live on ‘streets’, ‘marg’ or ‘roads’ : they live on ‘drives’. In the photo on the left, a house on ‘palm drive’. I might as well be somewhere in coastal california, or Florida, surrounded by multi million dollars villas.

What can these small casemates and tall gates be hiding?

An aerial view never fails to put in perspective things we don’t see from the ground – in that case, how extremely lush and green Sainik Farm is, compared to the neighbouring Sangam Vihar

Once you manage to get past the large gate, you’re greeted with an impeccable lawn and a detached house, a coveited good in Delhi, a bustling city of 25 million. What the houses lack in taste, they have it in green.

Good Sleep…

…or just rest

Parks in delhi are some of the only public places where you can expect to find some calm, even silence on rare instances, and enough tranquility to take a nap, in the conforting shade of wide, towering trees. Many people practice this art of sleeping at any time, any place in any position and I’m all for it.

Central Park, Connaught Place.

Green dreams, Central Park, Connaught Place.

Ornamental Garden, Hauz Khas Park

A man sleeping in Vasudev Ghat, a park in construction when I took his photo, nearby the Yamuna river, north of Kashmere Gate.

Eternal Rest, Barber’s Tomb, Humayun Tomb Complex

Fighting the heat

Urban parks and forests are a key element in the fight against the urban heat island effect, a dangerous phenomenon produced by the concrete and built up areas absorbing heat in cities and increasing the local air temperature. On a walk on the bank of the Yamuna, I met Dheeraj, using a leaf as a fan, laying down in the sand and certainly not expecting someone to trouble his rest.

He may have been for 10 minutes before I came, or maybe the whole day. I’ll never know.

Ornamental Garden, Hauz Khas Park

Not just in India but in most cities on our planet, poorest neighbourhoods tend to have less green spaces by area and per inhabitants. The scarcity of trees and parks, which cool down the air locally and allow people to escape the heat, is one dangerous ingredient in the lethal cocktail of heat waves, sweeping across many developping countries without access to properly insulated buildings, parks and air conditionning. Morever, their inhabitants are more likely to do physical labour and work in the streets, or in the fields, increasing even more risks of heat strokes.

Excess heat caused by the urban heat island effect in Delhi was measured to be as high as 7.6°C in some neighborhoods during summer.

In may 2024, parts of Delhi experienced temperatures over 47°C, the kind of heat that can cause heat strokes and kill the most vulnerable. These record breaking temperatures are bound to be more and more frequent as climate change worsens. Green spaces are not some urban planners’ whim.

Green spaces matter.

Lawns along Rajpath and families enjoying a green and refreshing moment in the hot late afternoon.

This leaves us with a question:

what is the geography of parks, gardens and more generally, just trees, in Delhi?

In this other map, let’s have a look at Delhi and most of its neighborhoods (wards), how green they are (any type of vegetation included but more specifically trees and large plants) and how much of their areas is actually made up of parks, gardens, golf courses, public-friendly / walkable forests or woodlands…

As mentionned earlier, when it comes to trees and parks, all places of Delhi are not equal: you can easily spot the poorest neighborhoods just by the light colour, colours that show that most of the area is built up or just bare land (the former accumulating a lot of heat during the day), while the South of Delhi and some other excentric localities are well endowed with parks, partly thanks to a proper urban planning, as opposed to informal / illegal settlements where no space is kept for parks and human density is much greater.

A lesser known green space of Delhi: the Yamuna Biodiversity Reserve, a successful initiative to restore a wetland that now serves as an habitat for migratory and resident bird species, on more than 450 acres of land.

The reserve is also designed to conserve the wild genetic resources of agricultural crops and enhance groundwater recharge and improve freshwater availability, as it is located on the Yamuna flood plain.

These natural, wild areas, don’t just help reduce heat on a local scale but are also havens for animal species that can thrive and use these patches of vegetation as corridors.

Old stones, young leaves

Gardens and historical landmarks have a long, shared history in Delhi. All rulers, from the Delhi Sultanate, the Lodi Dynasty, the Mughal Empire and the British Raj, took pride in building beautiful gardens and celebrating nature, as a refined form of art and discipline, creating beautiful dialogues between the stones and the trees. The Persian Char Bagh (four garden layout) represents Paradise in the Islamic tradition, nothing less while the british

Because of Delhi’s history, most of the city’s iconic gardens feature tombs or are inside forts dating from the 12th to 16th century, built in a Persianate / Mughal Architecture. The visitor will find these old red quartzite, sandstone, brick or marble buildings nested in lush, delicate and flowery gardens. One goes with the other, almost naturally.

Humayun's Tomb and the most striking example of Char Bagh in the city

Women working in Lado Sarai Flower Nursery - Qutb Minar in the background

Sunder Wala Burj - Sunder Nursery

Indian Habitat Centre

The Sunheri Masjid, surrounded by Neem trees

Qutb Minar and surrounding lawns and bushes

Safdarjung Tomb with Royal Palm trees - a non native species, wide spread in Delhi, that is critised for its water consumption, among other things

Shahi Masjid

Maqdum Sabhzwari mosque and tomb

Bagh-I-Alam Ka Gumbad, Deer Park

Indian Habitat Centre

Raj Ghat - Gandhi's Memorial

Humayun's Tomb

A Banyan growing on the medieval wall of Delhi, one of the very few remaining parts of it

Sunderwala Burj as seen from the entrance of the park.

Sunder Wala Burj, a 16th century building in Sunder Nursery, is a park located on the legendary Grand Trunk Road. It was renovated in 2018 and contains over 300 species of tree, thus becoming Delhi's first arboretum.

Sunder nursery is a garden of particular importance for our topic: it was the place where the British brought seeds from their colonies—so basically from every corner of the world—to conduct botanical experiments, grow saplings and beautify the freshly built New Delhi with exotic trees. The photo below shows hundreds of pots and saplings under the shade of a mature trees.

Playful dogs walking away from Mirza Muzaffar Hussain’s Tomb, Sunder Nursery.

Chlorophyll and power

Gardens and green spaces are more than beautiful botanical arrangement of trees and flowers that speak to artisitc sensibilities: they are places where power is demonstrated in a very eloquent and articulated way.

The landmark attracts thousands everyday and from its two large sandstone legs, a large avenue unrolls: the Rajpath (formerly known as the Kings Way) dotted with trees and lawns. It is 2 kilometers long, bordered by official buildings like Ministeries, the National Museum or the Parliament and each year, military parades walk along it for national festivities and ceremonies.

Actually, one small part of the Estate’s garden, Amrit Udyan —formerly the Mughal Gardens due to its Char Bagh design— is open to the public during a specific time of the year, a few weeks of spring, when all the flowers bloom under the towering figures of the buildings designed by Lutyens more than a century ago

The India Gate (and the surrounding India Gate Park) is a monumental arch built in 1931 by the British, soon after New Delhi was built and became British India’s capital.

Rajpath was built by the British and, unsurpisingly, feels very European in design and aesthetics. So European in fact, that as a Frenchman it can’t fail to remind me of Paris and its most famous avenue, the ‘Champs Élysées’. In the second half of the 19th century, Baron Haussman cleared slums and medieval houses in Paris to make way for wide, long, straight and geometrical avenues piercing through the heart of Paris, creating tall, uniform buildings and freeing up space for parks and gardens that we know today and are part of Paris’ urban identity.

See the full map at the beginning of the article

Reasons for this radical urban decision were partly hygenic, related to the beautification of the city. But most importantly, it was about Order. This was a way of keeping the protesters and revolutionaries in check, as heavy social turmoil was a regular occurence in the 19th century Paris, with its many narrow, winding roads and dark alleys.

Pictured here, the Rashtrapati Bhavan—the President’s Estate— also built by the British, a highly authoritative building surrounded by fantastic gardens shown below. As indicated by this barrier, this is the line where the greenery switches from ‘public’ and ‘free’ to’ VIP’ and ‘restricted'.

Gardens and wide green spaces also happen to be the perfect place for display of tall and visible flags, a very common sight in Delhi, even in small and local parks, shared in a residential block (with flags matching the park’s scale in size). Pictured here, the 9 by 18 m flag, the largest one in all of India, located in Central Park (Connaught place).

On the right, the windows of the metro station Rajiv Chowk, one of Delhi’s busiest metro station that goes just underneath the palm trees and tranquil wanderers of the park.

Health

Here’s another great power trees and green spaces are endowed with: providing a space for exercising and well being, especially in cities where they offer some respite for the heart and the soul.

Concrete and leaves: when the mineral and vegetal worlds merge and coexist, with urban humans intersecting in the middle.

Men in their forties or older often meet each other, same age and same colony (the indian english word for urban locality or neighborhood) during the morning for various exercises meant to improve mental and physical health.

Here, in this small park of Ashok Vihar, these men are chanting a mantra to Krishna just after completing 5 minutes of laughter Yoga that I could hear from my balcony, which triggered my curiosity and made me come.

They will say then goodbye to each other and take leave until the next morning for the same ritual.

Built on what used to be the Yamuna floodplains, an important natural buffer zone increasingly encroached upon, the Yamuna park is a lively area built under the noisy ring road, north of the city.

The place stills provides calm and soothing sights, where people from the nearby tibetan refugee colony of Majnu ka Tilla come to exercise and meditate every morning.

A man meditates under the shade of a large tropical tree, a thousand of year old scene, recreated in 21st century Delhi.

Pranayam Yoga, a form of Yoga that focuses on the breath, is mentionned in the two thousand year old Bhagavad Gita but hasn’t lost any of its popularity today.

Inspiration

Artists of all time have been inspired by nature and some of the finest painters of the early 20th century such as Monet, Renoir, Van Gogh, Cézanne and others were drawn to gardens where they found inspiration and beauty in vegetal shapes, flowers, trees, their colours and the atmosphere you find in places filled with them. Artists of Delhi are no exception!

On the other side of the same building, Bada Gumbad, I meet an artist, Anubhav Priya who decided to build a camera himself. It is a camera obscura, as he explains to me, built in the most rudimentary but ingenious way, using cardboard, tape and a basic lens to take photographs of the monuments of Lodhi Gardens with a process known as cyanoptype.

On the third side of Bada Gumbad, I meet two art students sketching the beautiful dome, Gumbad in Persian, of the 15th century monument. One building, three pieces of art.

Cycles

To end this visual walk through Delhi’s trees, plants, gardens, and people we find in them, here’s a last green moment with Prem Singh, a farmer I met in the middle of a mosaic of green crops on the Yamuna floodplain, north of the city. He is a 74-year-old retired government worker and has been growing food for 60 years. 60 years, 60 cycles. We see him sorting spinach leaves, with the Signature Bridge as a backdrop, crossing the Yamuna river.

Nature in a megacity like Delhi can seem pretty tamed: rivers confined by concrete embankments, elegant bridges arching overhead, air-conditioned interiors sealed from the heat, wide roads slicing through space. And yet, every summer, during the monsoon, the city is reminded of how fragile this control truly is. The forces of rivers, mountains, and rain converge, and nature reasserts itself with sudden violence. The Yamuna, like many rivers in the subcontinent, swells and spreads, overflowing its banks, swallowing vast stretches of floodplain. In doing so, it renews them—depositing fertile silt, nutrients, and, inevitably, the pollutants carried downstream.

Prem Singh’s crop is no exception: the very first civilizations emerged on river floodplains, and the cycle has continued ever since, an age-old cycle that has been unfolding, every year, for thousands of years. So many years, so many summers have seen the black clouds of monsoon rain gather in the angry skies and when they burst, feed rivers and make the city green again.

A group of fashion design students are taking pictures of a fellow student wearing clothes that they designed, inspired by the Apsaras, mythological hindu nymphs, with the Bada Gumbad of Lodhi Gardens as a background.

See the complete photo gallery of these two months I spent in India

What if all the glaciers melted? See a new map of India