THE COLORADO

Unlike other entries from the series, the Colorado River is not just a river-tree, it’s also a tree-book! The geological history of this iconic US river is incredible: with the sheer force of its branches, it has shaped not just one spectacular canyon—the world-famous Grand Canyon—but several: Glen Canyon, Cataract Canyon, Ruby Canyon, and Marble Canyon. These canyons are like open books on the geology of our planet, much like the rings of hundreds of millions of years old trees that we can read to learn about past climates and extinct flora and fauna...

The Grand Canyon is immense, like the world tree to which it owes its existence: approaching 1,600 meters in depth in places, it is 450 kilometers long and spans nearly 5,000 km². The Colorado River, with its sharp branches, carves into the rocks like a master carver, using only the force of its current. It reveals the passage of geological time as it flows: the rock is eroded by the passage of water and the riverbed sinks into the geological strata as the water flows, reaching rocks 1.7 billion years old at the climax of its course!

The Colorado is one of those giants that has exerted a powerful attraction in the North American imagination with the beauty of the landscapes found along its branches and the symbol it embodies. But beyond this tourist image, what else is there?

It is tempting to compare the colorado to the Yellow River, Styphnolobium Huanghensis : it too owes its name to the colors of its turbulent, sediment-rich waters: colorado means colorful in Spanish. It too has enabled life in a hostile environment and, finally, it too is a tree with a weakened trunk and withering roots: humans are draining so much sap from it that it barely reaches the sea today.

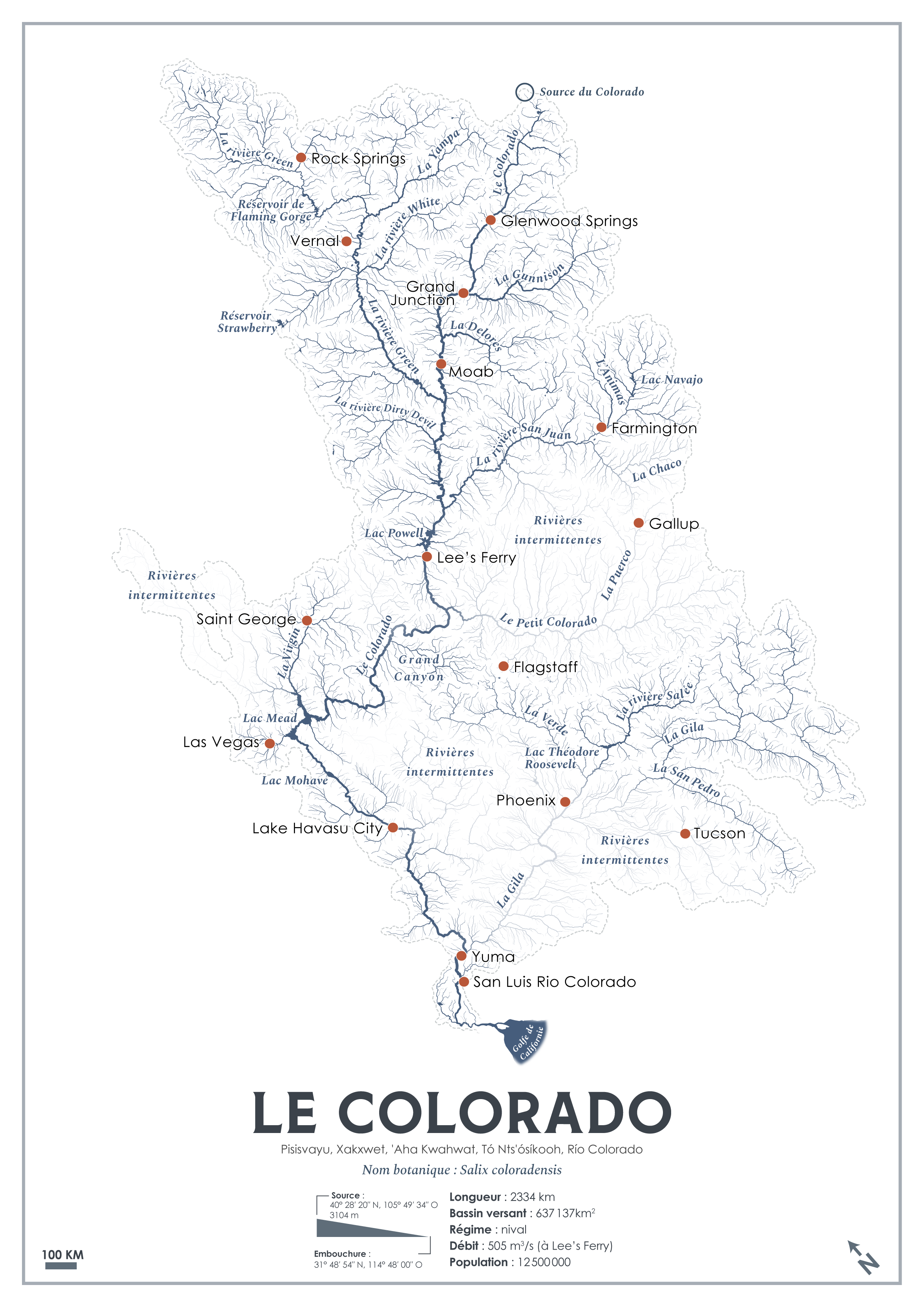

Increasingly snowless winters and increasingly scorching summers, coupled with the voracious appetite of humans and their irrigated crops downstream, pose a real problem for the 40 million Americans and 28 indigenous tribes who depend on this water. For more than a century, the river has supported rapid economic growth in the southwestern United States. Agriculture and energy produced by hydroelectric dams have been real drivers of growth, but we must be careful not to saw off the branch we are sitting on. The map shows this clearly: some branches, entire parts of the tree itself, are fragile and dormant, lifeless for much of the year and only filled with sap and life in the spring. Cut off this vital flow and beware of the consequences!

As evidenced by the few names given to the branches of the river, many indigenous peoples have flourished in the branches of the tree. Some saw their famous cliffside cities and cultures suddenly decline after overusing wood resources or suffering intense droughts year after year. The Shoshone, Paiute, Ute, and Mono—indigenous peoples of the “Great Basin”—know this: when life hangs by a thread (of water), you mustn't pull too hard on it.

Goodding's willow, Salix gooddingii, would be a good choice to represent Colorado. The species is native to the American Southwest and named after Leslie Newton Goodding, a 20th-century American botanist considered the foremost expert on the flora of the Southwest at that time. In addition, the tree thrives near rivers, in wetlands saturated with water from mountains and canyons, while its rough, raw trunk, reminiscent of the raw nature of the river, is extended by thin, graceful branches, reminiscent of the fine mountain streams whose flow is limited by the climate.