28th may 2054,

I just bought a one way ticket to Rio de Janeiro from Brest

Estimated time of arrival? In a couple weeks.

Brest, Port Monde

a tourist map from a post plane world

No doubt many of you have already been on holiday by plane, and after all, It’s no big surprise. We're all bombarded with ads encouraging us to travel by plane as cheaply as possible, while society places great value on far-flung holidays and our prevailing business model leaves no room for slow-paced travel, leaving people with the leisure and pleasure of going away for several weeks or months at a time. In this equation —little time and a far-off, exotic destination— the unknown is inevitably the plane. But it's a matter of changing one of the two parameters, or even both, so that sailing becomes a travel choice that makes perfect sense!

To achieve this transition, there is on the one hand an urgent need to decarbonise the way we travel —a return trip from Paris to New York produces 2 tonnes of CO2 per person, far too much to meet most of our climate targets— and on the other the need to change the way we live our lives to include more flexibility, longer adventures and a slower pace. There is a final need, perhaps less pressing, but one which does exist: that of experiencing once again the joy of the journey rather than that of the destination, the pleasure of the road travelled already being a journey, unlike the aeroplane, which is more akin to teleportation than to travel.

In short, there's a long way to go. But let's imagine what the end of that road looks like.

The sea went from being a peripheral space

to one of centrality, a busy interface

In this near future, in which a profound change in the way people travel has taken place, tourists opt to travel by boat to the southern hemisphere or to the coasts of Australia for their long-haul holidays. Everything would change, including the first stages of the journey.

Living in Brest, if you want to take a plane to an exotic destination, you have to go to Paris, and therefore spend at least 8 hours on the road, plus one or two hours to get from the centre to Charles de Gaulle airport. With departure terminals in the port of Brest, travel time would drop to 20 minutes. The ocean suddenly becomes a central space, an interface, a connected place, just as it was in the past when the great Atlantic coastal cities were key points of passage for scientists, tourists and immigrants.

Once you've taken this first step, whether you're a lucky Brest resident pedestrian or a Parisian, tired of the bus or train journey to the Grand Terminal du Ponant not far from the port, you'll need to find your boarding terminal. There are 4 of them: the Europe Terminal, the Quai des Amériques, the Asia & Africa Embarcadère and the Porte Océane, each serving a major region of the world. Each terminal reflects faraway places in its architecture, atmosphere, languages and ships, with the shores of the Rade de Brest and its silvery waters in the background. I'll leave it to you to picture how fantastic it would look like.

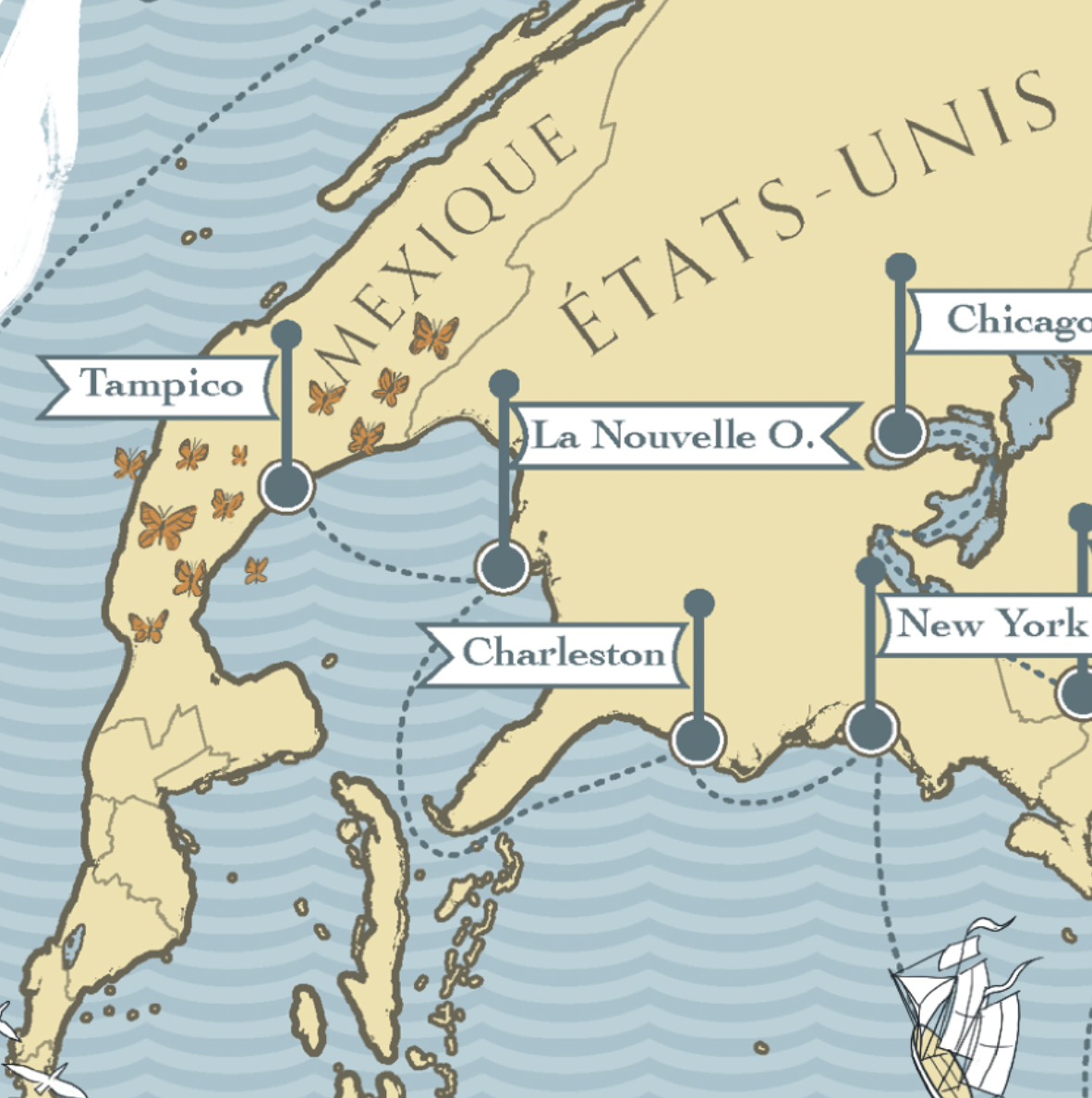

More than 58 destinations

This map, published by the highly fictional ‘Compagnie de la Penfeld’, a descendant of Air France, was inspired by a number of documents, including a map of the British Empire and, more generally, airline maps. It shows Brest in majesty, connected by the seas to 58 destinations on every continent, including Antarctica, honouring the city's strong ties with the polar regions. European cities and French overseas departments and territories are naturally well connected, and the frequency of departures from Brest decreases with distance. You have to imagine that in France, in such a future, few cities will play the role of port linking up with the rest of the world: Brest and Marseille in my scenario. Ships departing from Brest sail to the entire world, with the exception of the Mediterranean, which Marseille handles.

As the journey is inevitably longer than by plane, you need to count on stopovers if you want to get to India or Los Angeles: like a bus, at each stop along the coast, the ship will load and unload passengers, mixing nationalities at each port. From each port offering connections - such as Reunion, the Azores or Guadeloupe - tourists are then free to continue their journey further and further inland or hop on another boat.

Retro-futuristic ships

Obviously I'm not a naval engineer, but I've tried to come up with a more or less realistic idea of what these vessels from Brest would look like and how they would operate, cruising the seven seas all the time. In a word: wind. That's the ‘retro’ in ‘retrofuturist’ —that, and the very concept of travelling on a ship. The wind, that old friend. It's the wind that's going to make the ships arrive safely in port, thanks to their optimised technical sails, just like you'd find on the ships of real-life travel companies that have started to appear in the real world.

Where we really get into ‘futurism’ is when it comes to propelling the boats against the wind: there's no question of propelling them with fuel oil, as that would defeat the whole purpose of this project. I'm going to pull out my fiction joker card and offer as an explanation for these beautiful plumes of steam coming out of the chimneys, clean mini nuclear reactors. What's the point of making a fictional map if you can't chase wild dreams?

Here are the company's three flagships, combining sails and powerful engines: the Ponant, the Morlenn and the Armorique, which can carry hundreds of passengers on board, offering an unrivalled level of comfort for travelling around the world in style. They are inspired by magnificent historic ships such as the Great Eastern or the SS Great Britain, but modernised for our modern travel and tourism needs.

Disrupting advertisement

Airline ads, particularly for flights in Europe, are commonplace: on television, on social media, on billboards and in magazines. These adverts are relentless in their attempts to sell the experience of a world travelling at breakneck speed and an eco-suicidal form of tourism that offers visitors the chance to admire the beauty of the Andean landscapes while contributing to their decline by simply flying there.

What if we hijacked this tool, advertising and its powerful psychological mechanisms, to fill public place and people's minds with this new way of travelling? Let's not forget that my map draws its inspiration from airline advertisements and from a British Empire propaganda document, also designed to convince through images and storytelling. I am merely suggesting to repurpose the document with a different message.

A note of nuance: the beautiful ships are an excuse, a pretext, a beautiful image to talk about this bright future where travel becomes fantastic. Surely, we can move towards this ideal without necessarily reviving the age of sail, which I'm romanticising a little here, let's face it. It would in fact be an illusion to believe that the solution necessarily includes travelling by boat, but the image of a three-masted ship leaving port, sails aloft with all that human energy on board, is simply too beautiful not to be used for this story.

Homo itineris, a travelling species

Human beings are wanderers by nature. The ancient spread of our ancestors from tropical Africa to temperate zones, arid deserts, high plateaus, and distant islands is a testament to our deep-rooted impulse to move. For most of our history, we lived as nomads, attuned to the rhythms of the seasons and the generosity of the land. In many ways, we were not unlike the creatures featured on this map: Arctic terns, sea turtles, blue whales, monarch butterflies, storks, species that journey thousands of kilometres each year.

It’s worth remembering our animal nature, to understand where we come from in order to imagine where we might go. It’s a cliché thing to say, perhaps, but on a travel map, it feels especially relevant.

Reembracing, even partially, a nomadic existence—a life shaped by seasonal migrations—could be a great way to reconnect with nature and to discover in our short time on earth the planet’s thousand geographies. In becoming Homo itineris, we not only address growing issues linked to sedentary life—obesity, mental distress, social isolation—but also stand to gain something deeper: a renewed sense of wonder, intellectual expansion, and emotional connection.

The scenario I am sharing with you here imagines a world where travel is no longer a privilege or a carbon intensive pleasure, but a shared, sustainable practice, almost one that is a biological trait. To recreate a culture of travel that echoes our nomadic past is to rekindle that sense of awe and wonder along the road. Beyond the undeniable environmental imperatives, with figures and facts we can’t ignore, we must craft a new vision of movement, one that invites us to set sail, together, toward a different future.

“The wind rises, we must try to live”

Paul Valéry