THE AMAZON

Make way for the giant among giants: the Amazon. While the Loire is our great national river for us french people, the Amazon is the largest in the world — in terms of discharge, catchment area, forest and the imagery it inspires. An absolute Goliath, whose dimensions are beyond comprehension: more than 6 million km² of watershed, or 12 times the size of France, and a flow that alone represents one-fifth of the planet's river water.

The river is the central axis of a world tree, inseparable from the largest tropical forest on Earth. This Amazon River-Tree is watered by the famous atmospheric rivers, air currents saturated with water evaporated by the forest itself. The water rises, travels, then falls as rain, completing the cycle that feeds the trees and rivers once again. This forest is fertilised by winds from the Sahara, which bring a little African dust with them. It is a huge but fragile organism: every year, millions of hectares disappear, cleared to grow soybeans, among other crops, and feed the world's livestock.

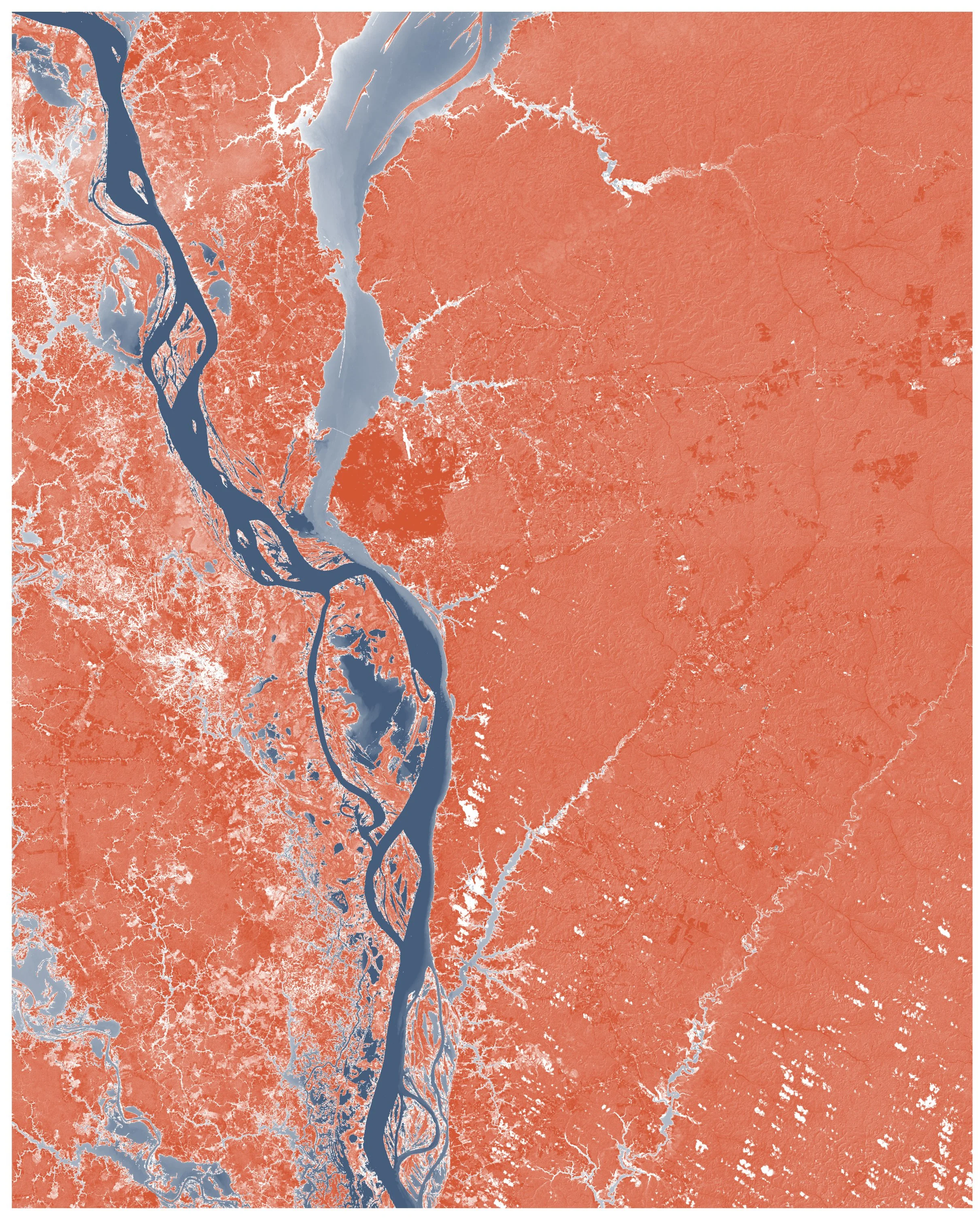

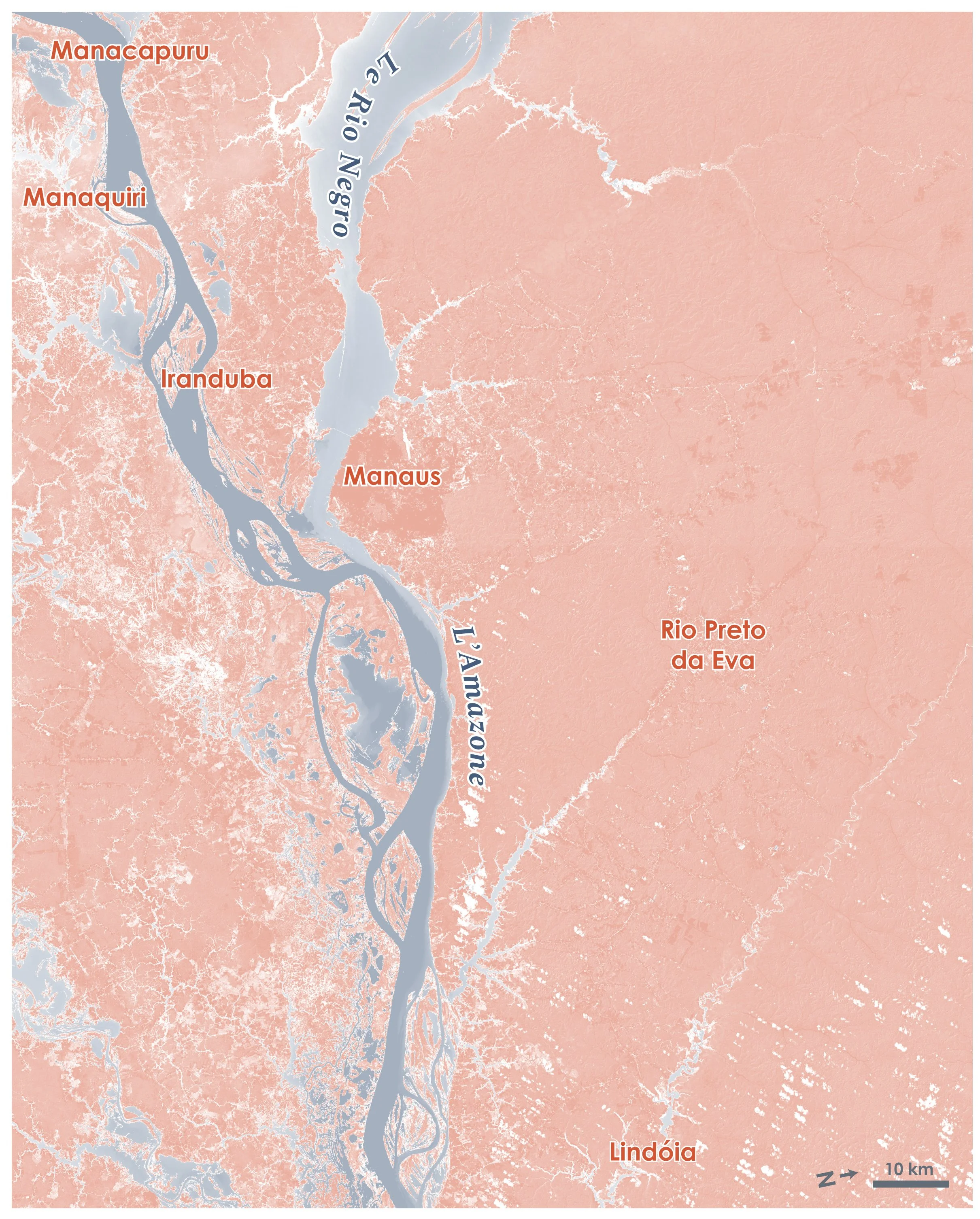

There are not enough superlatives to describe the Amazon. Its flow rate reaches 209,000 m³/s at the estuary — compared to just 1,000 for the Loire. That is 210 times the flow of the Loire. The river can be up to 10 km wide, and in its lower valley, the other bank can only be seen on a clear day. Its nickname, ‘river-sea’, given by the indigenous people, takes on its full meaning. Its Strahler index — which measures the complexity of the network — is 12, a world record.

Its headwaters? They begin in the Andes, at an altitude of 6,000 metres. From there, a thousand tributaries feed it, scattered in Ecuador, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, Venezuela, Brazil. Among them, the Rio Negro, a black river laden with tanins from fallen vegetation and leaves giving it its black colour, contrasts with white rivers such as the Rio Branco, which carry sediments stripped from the mountains. Some of these rivers flow parallel to each other within the same river bed without mixing for miles, a fascinating phenomenon. When all these tributaries come together, the trunk of the Amazon tree takes shape. It takes root in a shifting delta, a world of water and wood, of stilt houses, where salt water is rising higher and higher, threatening the villages. Mangroves, with their extravagant aerial roots, line the banks. They are at once a filter, a shelter, an anchor and a symbol. It is here that the river prepares to meet the ocean.

Perhaps the most poetic phenomenon is the Amazon plume: a trail of fresh water at the mouth of the Amazon, pushed by ocean currents towards the north-west, all the way to the West Indies. A network of liquid roots reaching out to other islands and shores, carrying sediments, nutrients... and pollution.

If the Amazon were a tree, it would be a mangrove. It too has its feet in the water, absorbs salt, stores carbon and shelters life. It is made for floods and the amphibious world.

The Amazon mangrove tree, Avicennia Amazonia